The gap between propaganda about Palestine in contrast to the reality I know as a Palestinian has made me wary… The most serious failing in political art is that it does not make clear whose side the artwork is on. When such clarity is lacking the benefit defaults to those currently in power.

—Samia Halaby (Arab Studies Quarterly, Spring/Summer 1989)

Punctuating several galleries of the Jewish Museum in Manhattan are the vibrant paintings of art world superstar Kehinde Wiley. On display (until July 29) is a selection from the Israeli installment of his ongoing World Stage series—an extensive body of work that was developed by identifying the global interpretations of hip-hop that appear in various cultural contexts. Wiley, who is admired as a postmodern liaison to hip-hop, created these portraits using his signature concept of exaggerating the grandiose visual tropes of European historical painting. Prior to launching this recent series—which has taken the Los Angeles-born painter to India, China, Senegal, and Brazil—most of his portraits were of young black men who were recruited from the commercial thoroughfares of Harlem and downtown Brooklyn.

By instructing his subjects to adopt the theatrics of official portraiture while dressed in “urban” street clothes, Wiley’s work is understood as summoning the perceived signifiers of posturing that have been vital to hip-hop since it first emerged as a concrete subculture through music, dance, fashion, and art in late 1970s New York. Interplaying two foreign, yet seemingly akin, social phenomena, the artist maintains that his primary target is Western art history and its frequent exclusion of black protagonists.

Recently, he has expanded his focus to include young men of color from emerging international hotspots. In the World Stage, he often turns to site-specific imagery for visual references, namely that which signals a dominant narrative—be it the underlying rhetoric of public statues that depict political leaders, or instances of local cultural patrimony that reflect the glaring tensions of symbolic attributions of power. This is combined with bright floral designs that surround his figures as backdrops to the artificiality of mock historical moments, arranging their bodies into the recesses of his settings.

In the artist’s “Israel” paintings, he departs from this focus by steering his use of visual referencing away from such allegories. Instead, his portraits of Ethiopian Jews, Palestinians, and Israeli-born Jews are rendered with patterns, symbols, and compositional details from Jewish ceremonial art. This new element is possibly the most interesting to result from the entire World Stage series. If the conceptual lens that Wiley employs in previous works is applied, then this latest sampling of visuals constitutes the context in which his subjects must negotiate their individual identities. While the politicization of Judaism under the Israeli state is suggested through the use of such patterns and symbols, he also places special emphasis on the ethnicities of his models through prescribed imagery and texts.

A short documentary that is featured alongside these paintings shows his Ethiopian subjects discussing the racial discrimination that they endure as African immigrants. Given that the film is screened to provide background for the exhibition’s visual references, this leads the viewer to conclude that the overarching framework of these compositions is the political positioning of race within Israeli society. It remains uncertain if this is the artist’s actual objective, as he never commits to defining the critical parameters of his critique, in true postmodernist form. Thus, what might be visually provocative steers clear of upsetting the status quo, and conversely facilitates the projection of the status quo without inciting critical debate.

At the Jewish Museum, his large-scale portraits are hung in dark rooms that are spotlighted with atmospheric lighting—an effect that exaggerates the eye-catching, near-florescent palettes that accentuate his figures. This also works to direct the viewer to an emphasis on tonal variations in flesh, as a sort of drama and dimension is added through highlights and shadows that lend to a sculpted sense of realism. These smooth surfaces take on an additional formal function, acting as a place for the eye to rest amidst the dizzying complexity of patterns that have been taken from magnificent historical pieces.

Wiley pairs these canvases with the inspiration for his elaborate designs by selecting a number of examples of religious art from the museum’s collection. These cutouts and tapestries from North Africa, Europe, and Central Asia point to a visual culture that expanded and evolved over centuries (much like the development of Islamic art), as it was carried to various parts of the world through the diaspora. Initially serving to translate the spiritual, this primary aesthetic later provided the foundation for departures into social issues such as notions of identity, especially when introduced to new environments.

The pairing of his contemporary works with such artifacts is telling of the types of connections that the Jewish Museum is actively encouraging. Through a number of recent exhibitions, it has attempted to diversify its audience and expand its emphasis on points of cultural convergence. In its permanent collection, the museum covers a wide range of art and objects that chart the many transformations that have defined the history of Judaica. Ceremonial objects are thus placed within the same broad-spectrum context as modernist painting and contemporary photography and installation. This discursive approach reflects one of the many burdens of operating an institution that remains on the margins of American culture despite being located in a major city-center. Like El Museo del Barrio and the Studio Museum of Harlem, the Jewish museum is thus faced with the task of assuring that particular histories maintain a visible presence as it advocates for today’s artists. To stay relevant, and to compete with larger museums, it must also envision creative ways to impact the future as it engages current trends. “The World Stage: Israel” exhibition seems to have been organized with much of this in mind.

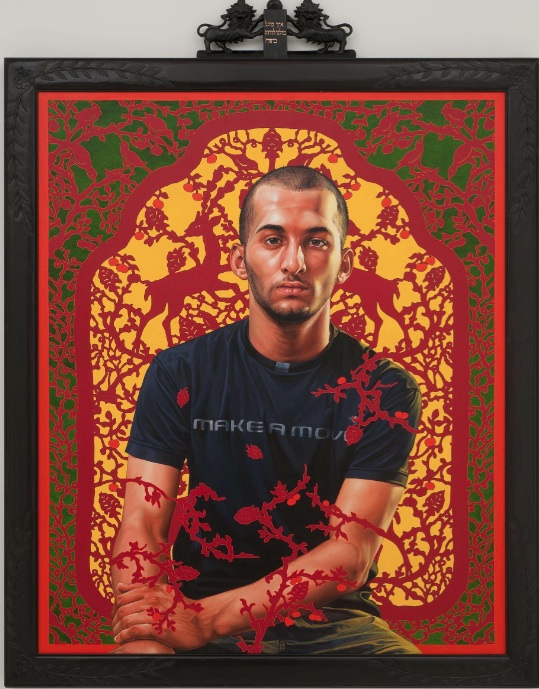

The first painting that the viewer encounters upon entering Wiley’s solo show is “Mahmud Abu Razak” (2011), a portrait of a Palestinian man whom the artist recruited in 2010 while sourcing models in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Lod. Abu Razak is seated with a frozen stare. A red cutout pattern wraps around his upper body, appearing animated as it spreads to the foreground. Set within solid color fields of yellow and green with an inner border of red that is accentuated by the black of an outer frame, Abu Razak is placed against a palette closely resembling the Palestinian flag (with yellow being used in place of white). To sympathizers of Israeli policies, this color scheme can be overlooked as a mere coincidence when read according to the compositional traits that are reserved for “Arab-Israelis.” As the artist’s remaining portraits leave little room for the assertion of a Palestinian political identity, “Arab-Israeli” is the preferred description throughout—a confirmation of the colonial project. Moreover, “The World Stage: Israel” is devoid of any actual mention of Palestine.

[Kehinde Wiley, "Mahmud Abu Razak" (2011). Copyright: Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California]

It is not that the Jewish Museum refuses to address the subject of Palestine in its programming. At the same time that it stressed an “elusive reality” in the 2007 exhibition “Dateline Israel: New Photography and Video Art,” the museum glossed over aspects of the occupation in its descriptions of contemporary works. Settlers led everyday lives in the West Bank; the annexation of Palestinian land was shown without question. The massive concrete wall that runs through the Jerusalem suburb of Abu Dis was simply a matter of citizenship, dividing “families and communities into Palestinian and Israeli Arabs.” The ancient olive tree (a long-held symbol of Palestinian culture and heritage) was stripped of its encoded meaning, reconfigured, and appropriated. Palestinians were represented, albeit with a contextualization that asserted the official Israeli storyline.

In “Liberating Blackness and Interrogating Whiteness,” Phyllis J. Jackson describes the absence of narratives as evidence of dominant political discourses within visual culture: “societal and cultural exclusions remind us that the realm of art making is enmeshed in the politics and culture wars at large” (Art/Women/California 1950-2000: Parallels And Intersections, 2002). This is most true of the Palestinian experience and how it is invariably ignored, silenced, or attacked in the mainstream art world.

Many of the themes that were central to “Dateline: Israel” were previously explored in the exhibition “Made in Palestine” (2003), resulting in corresponding images of olive trees, Israeli soldiers, checkpoints, Palestinians in domestic spaces, and sweeping landscapes. As the occupation was anything but normalized in the works of its artists and its accompanying wall texts, “Made in Palestine” marked a pivotal moment—the first time that the American art scene was forced to acknowledge the modern Palestinian narrative. Originating at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston, it later traveled to several cities in the US, including New York in 2006, where it was hosted well beyond its scheduled closing date. Despite media attacks and political outcries, many credited its overwhelming popularity to its alternative look at the lives of Palestinians. Unfortunately, the show in no way eradicated the prevailing attitudes that were active in trying to curtail it.

The mounting of “The World Stage: Israel” is noteworthy; it is not minor that portraits of Palestinians would be featured so prominently within the setting of a New York museum. Admittedly, it is surprising. However, this initial allure quickly dissipates when studying the semiotic nature of these compositions, which bolster the political dimensions and social constructs that continue to dictate discussions of race and identity in twenty-first century Israel (and America, the master prototype).

Wiley’s paintings of Jewish men are affixed with monikers that include the Ten Commandments in Hebrew, two lions of Judah, and two hands of a Kohen (priest), representing “power and majesty” and “blessing.” The power and majesty that is indicated through these identical anthropomorphic figures is also significant to the visual culture of Ethiopia as a reference to the Solomonic Dynasty, linking the historical ties of his African subjects to the notion of a Jewish homeland.

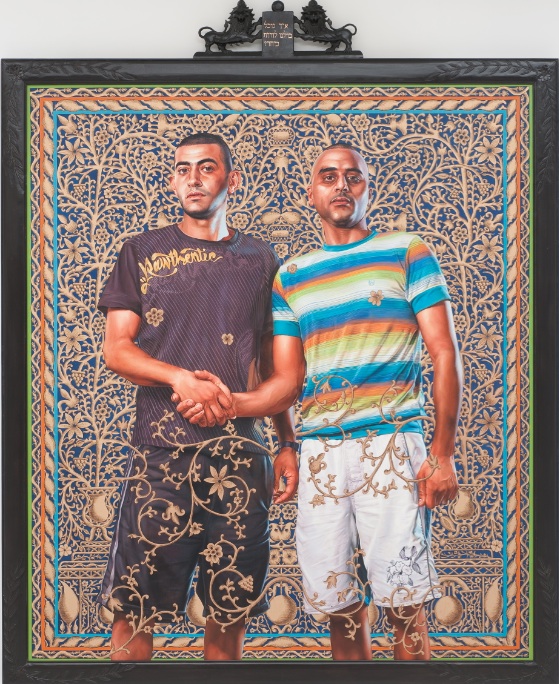

Depictions of Palestinians are crowned with the same twin lions minus the spiritual blessing. The text that brands their image is a Hebrew translation of Rodney King’s oft-quoted statement from the 1992 Los Angeles “riots,” “Can we all get along?” Each portrait of the exhibition incorporates a different design that has been meticulously copied from a traditional source regardless of the cultural or religious background of the sitter. Two-thirds of these images are of Ethiopian Jews.

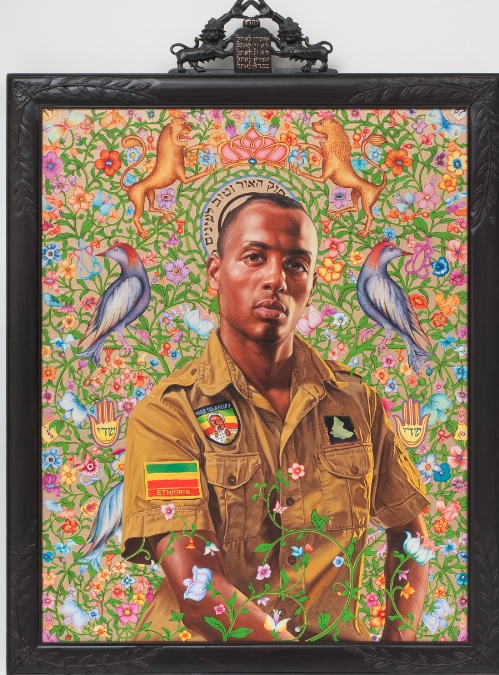

The first step in the artist’s scouting of “Israelis” was to find characteristics of a local hip-hop aesthetic. Initially, this manifests in the loose, casual clothing of his figures that is adorned with large, discernible logos and graphics. Without the additional surrounding imagery and titles of each portrait, the viewer would be hard pressed to distinguish these men from other youth who have adopted hip-hop fashion as it has permeated global culture. The exception to this common thread is seen in “Kalkidan Mashasha” (2011), which depicts an Ethiopian hip-hop artist who produces “raw, lyrical raps about his Ethiopian-Israeli Jewish identity.” Mashasha wears a khaki button-up shirt in the vein of the Afro-centric/socially conscious style that was at its peak during the “golden age” of hip-hop in 1980s and 90s America. Such decorated military fatigues worked to generate an aesthetic connection between past class-based revolutionary struggles (think the Cuban Revolution and the Black Power movement) and the concerns of influential rappers. Mashasha is shown adopting this appearance as an expression of his Ethiopian identity.

[Kehinde Wiley, "Kalkidan Mashasha" (2011). Copyright: Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California]

Set against an intricate flora and fauna motif, he is depicted before a circular Hebrew emblem that reads, “How sweet is the light, what a delight for the eyes to see the sun.” The emblem is placed within the composition so that it appears as a halo, an obvious reference to the motifs of Christian iconography. On the surface, Wiley’s use of such visual rhetoric recalls a significant lineage within modern and contemporary art that has sought to deconstruct the aura (as theorized by Walter Benjamin) of portraiture in Western art history by removing the iconification of imagery from its religious dimensions or substantiated power structures. A number of his paintings utilize this distinct take on the genre, as halos and blessings are bestowed on Israeli men. None of his icons are Palestinian.

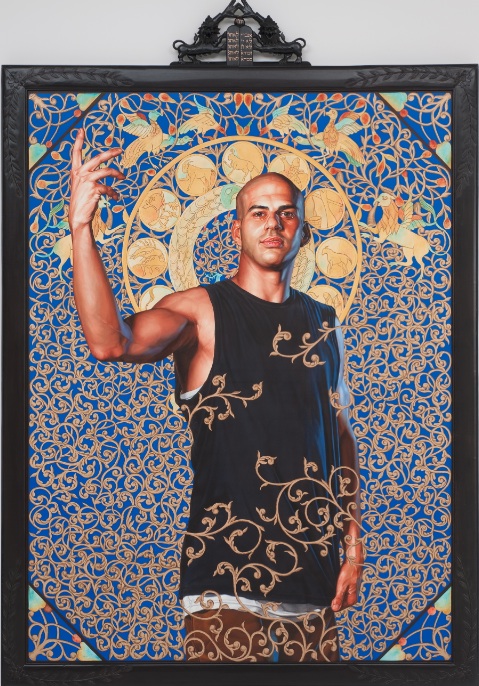

Within the series’ concept, Mashasha is given prominence as an unofficial spokesperson, voicing the experiences of Ethiopian men who embrace the Jewish state but are suspiciously looked upon as outsiders. At the time of the exhibition, this discussion of racial inequality as it pertains to the black communities of Israel could not be more relevant, specifically when official policies and public opinion towards non-Jewish African migrants grow increasingly hostile. Although Mashasha’s status as an outspoken rap artist places him at the center of the exhibition’s theme, it does not go unnoticed that the largest halo in this cast of icons is actually given to the “native-born” Jew of another painting. The man who stands before the golden chart in “Leviathan Zodiac”(2011) exudes swagger with an exaggerated pose. In reading his usage of symbolism, traces of Israel’s fixed racial hierarchy pervade Wiley’s overall representation. Ethiopian Jews struggle for acceptance and power; “native-born” Jews affirm their natural-born power; Palestinians are rendered powerless.

[Kehinde Wiley, "Leviathan Zodiac" (2011). Copyright: Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California ]

[Kehinde Wiley, "Abed Al Ashe and Chaled El Awari" (2011). Copyright: Kehine Wiley. Courtesy of Roberts &Tilton, Culver City, California]

Whereas the assignment of Rodney King’s plea to Palestinians might seem superficial, or even naïve, when viewed within the artist’s formulation of visual codes, this statement is quite unsettling. In the double portrait “Abed Al Ashe and Chaled El Awari” (2011), two Palestinian men are shown side by side, their arms extended in a forced handshake. Supporting King’s words, the painting is reminiscent of the media coverage that often accompanies a political agreement between two opposing parties, a minor physical act that is staged and recorded as a monumental moment. Edward Said’s description of the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 comes to mind:

The vulgarities of the White House ceremony, the degrading spectacle of Yasir Arafat thanking everyone for what, in fact, was the suspension of most of his people’s rights, and the fatuous solemnity of Bill Clinton’sperformance—like a twentieth-century Roman emperor shepherding two vassal kings through rituals of reconciliation and obeisance—all these only temporarily obscure the truly astonishing proportions of the Palestinian capitulation. (Peace And Its Discontents, 1996)

["Bill Clinton, Yitzhak Rabin, Yasser Arafat at the White House," (1993) Image by Vince Musi]

In interviews, Wiley often stresses his interest in the idea of spectacle. The act of recreating historic European portraiture—with its dramatic poses, lavish textiles, and embossing of regal men with aestheticized power— facilitates the place in which such moments are forged. As the simultaneous director, designer, casting agent, and manager of this stage, the artist retains a strategic role, remaining unscathed and unaffected by the type of “spectacle” that Said identifies. Scenes of “capitulation” not only play out in paintings of Palestinians whose images are muted; they are intensified in his portraits of African American men.

When examined in a contemporary context, the customary signs of antiquated official portraits seem outlandish and silly. Jacque Louis David’s “Napoleon at the Saint Bernard Pass” (1801) stands as one of the most recognized examples of this school of painting. Its reliance on a false sense of drama, manufactured heroism, near mechanical precision, and emphasis on decadence are characteristics that, if approached with seriousness, now border on Kitsch. This is due to decades of work by artists who carefully dismantled the social constructs that are evident in the tradition. European Modernism was very much about chipping away at these forms, turning to non-Western visual cultures for guidance while earth-shattering technology inspired advanced ways of seeing. The figure, more specifically, was the primary target of such investigations; and when not completely taken on formally was transformed along class lines.

Modernism’s arrival to the US in the first part of the twentieth century occurred as ongoing social polarization was coming to the forefront of national discussions. Against the backdrop of avalanching economic disparities, American artists were selective in their application of modernist techniques. The spotlighting of racial inequality became inherent to explorations of class. Thomas Hart Benton, Aaron Douglas, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi were heavily involved in this conversation, utilizing figurative painting to contest the notions of beauty and power that had been part and parcel to Western art for so long. Through work that gave credence to the everyday lives of ordinary Americans, many artists demanded a more populist approach to art. This stood in antithesis to a turn of the century style that was committed to the Grand Manner of European painting with idealized depictions of the elite.

African American artists expanded these critical experiments throughout the twentieth century, engaging their efforts with social movements that proceeded to redefine national culture. As each key moment of modern political determination called for refashioned identities via new forms of collective struggle —from the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s to the Black Power movement of the 1960s and 70s—each successive era informed the work of artists. At different (and often overlapping) intervals within this long period of revolt, Aaron Douglas, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, and Barkley L. Hendricks, among others, all rightfully understood that creating art within the framework of American visual culture was a political act in and of itself. In the 1970s, vital cultural nexuses underwent a state of crisis as the fervor of the Black Power movement waned amidst ferocious assaults by government agencies (which included political assassinations and the onslaught of the Prison Industrial Complex). Enter hip-hop as a broadening of this history of struggle with the potential for addressing the nuances of individual and collective identities through a fluid format that is yielding of time and place. A direct descendent of Black Power, many of its facets challenge predominant discourse as affirmations of dissent in the face of the US’ institutional mechanisms of oppression.

Wiley’s relating of the hip-hop aesthetic to the pomp and circumstance of historical portraiture exists in his paintings as something to ridicule—an altering of his American subjects that is palatable for the ruling class of the art establishment. The power that is obtained through the defiant posturing of hip-hop—namely through lyrics that insist on destabilizing the very apparatuses of the US’ ongoing economic segregation—threatens the vested interests of art world powerbrokers (certain gallerists, curators, patrons, and institutions) who benefit directly from this disparity. Interestingly, in his commissioned portraits of major rap artists, larger-than-life personalities seem to determine their own destiny.

Although it is no secret that he coaches his models, what is often overlooked is that the young men of his paintings do not set out to be lampooned in their everyday lives (which the artist essentially trespasses upon in his process of scouting). It is simply taken for granted by most critics, who continue to operate with the colonial assumption that if the black body is to be considered it must be reconfigured and consumed. Ironically, even Wiley is not safe from being typecast. Despite the visible class-lines that are drawn between the artist and his “urban” protagonists—the juxtaposition between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures of his paintings, as critics call it—in reviews of his work, it is routinely noted that he benefited from his Ivy League education. Recently, New York Magazine referred to him as “a bootstrapper from South Central who talks like a Yale professor (much of the time)” (“The New Art World Rulebook,” April 25, 2012).

A decade ago, Jackson’s assessment of the American art world also included the following critique of a developing strand of contemporary artists and art world professionals:

Far too many suffer from a serious form of cultural amnesia that allows them to depoliticize the historical transformation of our society and its artistic communities. They slip dangerously close to embracing the normalizing ideologies and elitist aesthetic arguments that originally catalyzed a generation to wage war against the image-makers and their images. It is not merely petty arguments over who makes the prettiest pictures. It is a tense struggle for power to define the beautiful, the good, the worthy in art—and by extension in life. (Art/Women/California, 2002)

Wiley’s compositions of African American men differ in that they do not reflect signs of full-fledged cultural amnesia. Instead, he frequently alludes to such historical transformations.

An observable connection is to the paintings of seminal artist Barkley L. Hendricks, whose 1960s and 70s portraits reflect the direct social impact of the Black Power movement on American culture. Hendricks’ figures are shown in confident casual poses, standing or sitting as though they were informally asked to pose for a photograph. This photographic quality is significant since, in the process of composing his paintings, he regularly utilizes a camera as a “mechanical sketchbook.” Realized in painting form, snapshot-like images become striking meditations on the convergence of culture and politics that is embodied in the poise of his models. Through considered uses of color, traces of classical realism, and imposing compositional design, he accentuates the signifiers with which black, white, and Latino men and women announce their individuality, pointing to a heightened understanding of social agency that is applied to the public realm. At the time of creating these works, his elevation of “snap-shots” of American life was groundbreaking in contemporary art. This was principally important to artists of color who were unconvinced that the image should remain a sanctified form through which racial and class-based hierarchies are reproduced as socializing agents on behalf of those in power.

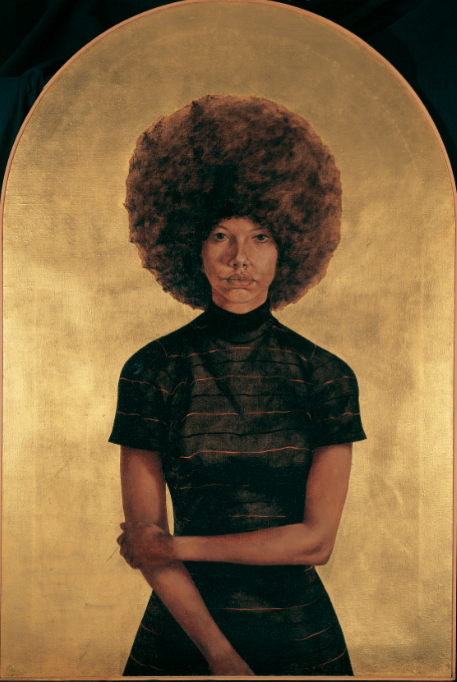

Hendricks’ 1969 portrait “Lawdy Mama” exemplifies the measured ways in which he approaches his figures. Giving attention to a conscious use of fashion as a component of their identity, he highlights the posture with which they pose. Noting minor gestures, he identifies the type of individual boldness that was crucial to the emergence of hip-hop just a few years later. The self-assured woman whom he renders with the likeness of a Byzantine icon in “Lawdy Mama” captures the defiant, near confrontational, confidence that was paramount to liberation struggles, an attitude that was often channeled as an act of solidarity among aligned political movements. The power she exudes is not from the artist’s placing of her figure within the setting of a religious icon; this marked perception and beauty is an aspect that is independently cultivated by his subjects rather than projected onto them. And in painting their images alongside a number of self-portraits, Hendricks places himself within this discussion.

[Barkley L. Hendricks, "Lawdy Mama" (1969). Copyright: Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.]

Examining “Mahmud Abu Razak” and “Lawdy Mama” demonstrates the frequent associations of Wiley’s methodical development of imagery to the concept and formal details of Hendricks’ portraits. Both subjects are presented looking directly at the viewer, their bodies shown in similar poses that are situated in golden semi-circle archways. Yet as images that rely on identity-icon paradigms to suggest multiple levels of meaning, they occupy opposite ends of the spectrum.

Questions of social agency arise when viewing Wiley’s portraits. At what point does the body become a basis for propagating elitist aesthetic arguments, as Jackson proposes? Judging from the positive reception to his paintings in the mainstream, cultural amnesia has as much to do with satiated viewers as it does with contemporary artists. Normalizing ideologies are reinforced when such representations betray their subjects and figures are turned into props (or objects).

A similar discussion on the role of art is taking place in the Arab world where buoying instances of uprising are surrounded by the omnipresent forces of co-option. Many cultural practitioners are calling for an increased focus on formalism as they publically bemoan references to the political in the work of Arab artists who exhibit on the fringes of fickle movements. What is unacknowledged, however, is that calls for formalist approaches devoid of the political are often accompanied by the uniform positions of class, privilege, and power that are constitutive to influencing artistic practices in market-driven art scenes. And in urging a new course, what then of the work of Palestinian artists who, as a result of the political and socioeconomic devastation that has been inflicted by the Israeli state and many Arab host-countries, have rarely had access to the psychic spaces to consider otherwise?

Just as Palestinian youth have found hip-hop to be an adaptable form that can transmit their realities (the importance of which Wiley completely ignores), a new generation of contemporary artists seeks to maximize the plasticity of postmodernism; most potently in conveying and challenging their political condition(s). The work of Jerusalem-based conceptual artist Raeda Saadeh is a perfect example, which often engages visual components of Western cultural history to subvert rudimentary notions of gender, the erasure of collective narratives, and the obstruction of political license. In a series of recent photographs, Saadeh elucidates the impact of the occupation by placing herself within compositions that are reenacted from European paintings and the fictionalized dilemmas of children’s folktales, adding a layer of complexity to the feminist critiques that inform her practice:

I often play the character of a woman living in a world that attacks her values, her love, and her spirit every single day. She is in a state of occupation. Her world could be in Palestine, where I live, or elsewhere… She may be weighed down by oppression, but she is filled with ambition; she is saner than she should be and yet she is also a little mad… And every move she makes, every act, exhibits an awareness of her environment while simultaneously being an act of revolt against social conditions. (Arab Photography Now, 2011)

In the 2007 work “Mona Lisa,” Saadeh has photographed herself as Leonardo da Vinci’s celebrated muse against the landscape of her native Palestine. Donned in a custom-made costume, she smiles wryly at the viewer. Scattered along this terraced terrain are pockets of Israeli settlements, hinting at the theme of this performance. As a Palestinian woman, she empathizes with this sixteenth-century Italian personality who appears physically confined to her surroundings but equally aloof. Both women attempt to go beyond the bounds of an imposed condition, if only in their minds. The artist’s critique of the occupation, which is not exclusive to land or a national reality, thus becomes intertwined with the constant sidelining of her being.

[Raeda Saadeh, "Mona Lisa" (2007). Copyright: Raeda Saadeh. Courtesy of Rose Issa Projects, London]

Several critics have referred to Saadeh as “Jerusalem’s Cindy Sherman” perhaps without realizing the ways in which such blanket comparisons essentially overlook her work (and her emphasis on addressing the situation in Palestine) with an association that deems it secondary to more visible narratives. A more appropriate observation is that Saadeh, like a growing number of artists, has found particular artistic approaches to reveal shared experiences among seemingly distant communities, despite the imposition of national, social, or cultural borders (which are fundamentally constructed and always subject to change).

Edward Said illustrates the concurrent states of occupation and revolt that are passed on to generations of Palestinians in an essay accompanying a series of documentary photographs by Jean Mohr:

I have never met a Palestinian who is tired enough of being Palestinian to give up entirely. Most of us still rally to our cause, even though a mixture of skepticism and fatigue (after all, how long can you go on losing?) breaks in whenever a new campaign gets under way… There is a notable stubbornness to these feelings that cannot be discounted. It derives from a sense of accumulated Palestinian history that is at once too public and too engraved in our current situation to be rolled back or ignored. Today, there are very few of us who can avoid the fate of every Palestinian, which is to be both there, and yet not be accounted for politically. (After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives, 1999)

Elements of what Said describes can be seen in the paintings of American artist Richard E. Lewis, whose portraits possess a reflective mood that is drawn from his subjects and the spaces over which they preside. As sitters are asked to pose within these domains with minimal interference on the part of the artist, his paintings are built around the body language of his models. Often depicted as warm and pronounced domestic settings, these interiors are neither the cold, bare Paddington studio of Lucian Freud nor the frenzied (enveloping) rooms of Henri Matisse. The majority of Lewis’ paintings are of his family and friends from periods that are split between New York and his native Detroit. A similar air of skepticism and fatigue is apparent in a portrait of his sisters, “Kim and Tonya Watching T.V.” (1997). Appearing at once guarded and at ease, they are unfazed by the slow passage of time that is involved with posing for a painting—in the same way that the quiet of this setting is undisturbed by the indistinguishable nature of the exterior world through an open window. In giving equal prominence to the surroundings of figures, he depicts spaces in which vivid lives are led in spite of the magnitude of an accumulated history that spills into the future.

[Richard E. Lewis, "Kim and Tonya Watching T.V." (1997). Copyright: Richard E. Lewis. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Richard E. Lewis, "James and Kelly" (1996). Copyright Richard E. Lewis. Courtesy of the artist.]

“James and Kelly” (1996), a double portrait that was painted during his residency at the Studio Museum of Harlem, depicts the artist James Reynolds and Kelly, his partner. The couple is seated before a wall that divided the painter’s studio from that of the late sculptor Michael Richards (who is shown in the background). This blocked space gives way to a composition that is anchored by the bold hues of vintage chairs that regularly appear in his paintings. A floral wall hanging and a white Virgin Mary figurine are additional relics from a small collection of personal items, which take on various roles as they adapt in meaning to the presence of different protagonists. Although James and Kelly are brought into a realm that is familiar to the artist and dotted with such items, they occupy a separate moment, one that is detached from the room and solely defined by the intensity of their awareness of each other. Wearing their own clothes, they seem to adopt the fashion of a bygone era of Harlem. In depicting this aspect with a painterly treatment of line and color, Lewis allows the confidence of the two men to take over the portrait, much like in the work of Hendricks. The pattern of the cloth in the mid section of the painting comes alive amidst this exchange, leaning towards them as though mirroring their intimacy.

Firmly planted in the politics of representation that feed the American art scene, Wiley is recognized as a prominent figure of the loosely defined “post-black” movement. Thelma Golden, the Studio Museum of Harlem’s director and head curator, is credited with coining the term with artist Glenn Ligon in the late 1990s after noticing a trend among established and emerging African American artists. A unifying point for many of this subcategory is that they resent and reject the art world’s penchant for categorization. This resentment is often directed at the efforts of their predecessors as much as it is towards the establishment. In undermining such identity affirming imagery while referencing the racial hostilities of Western visual culture, post-black demands a new postmodern approach to the exploration of black identity, one in which definitions are pushed to such extremes that they enter the paradoxical with the aim of making them obsolete.

A counterintuitive consequence of this approach is the formation of a new set of hegemonic standards altogether via the privileging of limited voices (and narratives) over others, and a presumed entitlement that forgoes any accountability in the securing of racist caricatures, stereotypes, and superficial understandings of identity. Champions of the this type of art often fall back on the so-called upward mobilization of African Americans over the past three decades, arguing that the identity-driven art that was influenced by the Black Power movement is no longer relevant. The mainstream art world is eager to chime in, citing lucrative careers such as Wiley’s (whose paintings sit comfortably in the six-figure price range) as evidence of social progress. In stark contrast, from 1970 to 2005, the US prison population increased by seven hundred percent with the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimating that one in three black men can expect to be incarcerated during their lifetime. Today, people of color are “disproportionately incarcerated, policed, and sentenced to death at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts” (“The 10 Most Disturbing Facts About Racial Inequality in the US Criminal Justice System,” AlterNet, March 2012).

During the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes warned against attempting to fit into the mold of “American standardization,” which offered the following bribe to artists: “Be stereotyped, don’t go too far, don’t shatter our illusions about you, don’t amuse us too seriously. We will pay you” (The Nation, 1926).